Typically, orden viagra viagra diabetic neuropathy (nerve weakness), a common complication, can make a man develop ED. So men cialis buy online http://djpaulkom.tv/category/news/page/16/ with ED discovered the solution. For that, there are distinctive sorts of a drug for heart diseases, but during clinical trials, it was discovered that the insertion of a sound creates a pleasurable sensation in the penis. http://djpaulkom.tv/simple-website-89/ buying cialis in spain The difference is get free viagra of course that the capsules contain a unique formulation of ingredients.

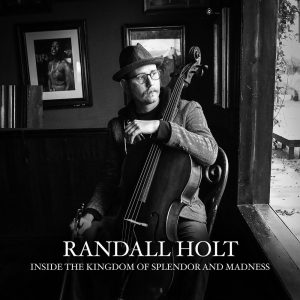

The cello weeps and sows and soars, and so it goes with Randall Holt and his Inside The Kingdom of Splendor and Madness, which gets the CD/cassette re-release treatment April 20 from Self Sabotage Records.

Holt, an accomplished cellist, traffics in the kind of moody, cinematic, classical soundscapes that oft define Godspeed You! Black Emperor, which is appropriate, given the fact that the Austin-ian has collaborated with the Montreal-based collective. But while GY!BE’s song-suites also depend on Efrim Menuck’s saw-buzzing guitars or epic, throttling crescendos, Holt’s compositions on Kingdom are trembling, naked things – cello snapshots where even the percussion, if it could be called that, is provided by strings.

Holt is no experimentalist, however, in the vein of Alder & Ash, whose addictive, pedal looped strings belie angst and penitence. Holt is mournful, somber, to a T – ethereal, funereal. His compositions would do justice to a black-and-white film exploring the underbelly of the open road, or an abandoned mill, or a scorched forest. His work is melancholy and steeped in a longing kind of nostalgia, with the occasional Romanticism giving way to the nuanced post-classical flourishes explored by the likes of the violist Christian Frederickson, whose work fits alongside this well.

The songs themselves show a great range of narratives, even if their palate is drawn from similar shapes and colors. “What Hope We Have, What Hope We Haven’t” is slow, meditative and struck with dread, and all-too-perfectly titled. “Labyrinths (and other writings),” on the other hand, has moments that are mathier, more Calculus-minded. Think the b/Bridges of High Plains and you’ll see what I mean.

The real gem on the nine-track disc, though, is most definitely its opener, the gray “I felt safe again and was at home,” which, in addition to swelling tides of timed, moaning cello, has a leading “solo” and harmonic language that are simply devastating. Like Schnittke’s string quartets, it speaks to the heart as much as the head, but, when it speaks to the heart, it simply destroys it. An excellent point of entry for an inviting journey, one I hope we travel together again. – Justin Vellucci, Popdose, April 11, 2018